Ayvansaray / Ξυλοπόρτης

- Lara Oge

- Mar 29, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2024

Ayvansaray is a neighborhood inside the city walls on the Golden Horn and on the northwestern side of the Historical Peninsula. The name of the town is commonly traced back to two stories: during the Ottoman Empire’s reign, livestock brought from abroad was kept here, and the neighborhood was called “hayvan sarayı,’’ meaning “animal palace.” The second story states the name comes from a combination of two Persian words, “iwan” and “saray.” Put together, the words mean “veranda palace,” which is a reference to the landmark Palace of Blachernae (τὸ ἐν Βλαχέρναις Παλάτιον, tó en Vlachérnais Palátion) that once housed the Byzantine emperors but is largely in ruins today.

In the fifth century, the sister of the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II, Aelia Pulcheria, built a church next to the Holy Spring of Blachernae. This was a defining feature that led to the erection of two more adjacent buildings within the next two hundred years. One of the buildings was the Hagios Soros Chapel, where clothing believed to belong to the Virgin Mary was kept. This became an attraction for visiting emperors, thus drawing further attention to the area. Over the next centuries, Ayvansaray increasingly became of interest to Byzantine rulers, and more religious and political landmarks were built. In the eleventh century, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos moved his residence to the Palace of Blachernae while also renovating and expanding the existing complex. The site where Pulcheria first established the church, which sparked a series of activities in the area, later became home to the Church of Saint Mary of Blachernae (Θεοτόκος των Βλαχερνών, Meryem Ana Kilisesi), a structure that still stands today.

The major changes in the neighborhood took place starting with the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Many churches were converted into mosques, and new ones were built, too. As a neighborhood under Ottoman rule, Ayvansaray became predominantly occupied by Muslims, who formed communities around the converted mosques. Two mosques prominent in such a way are the Kariye Mosque and the Fethiye Mosque, previously the Khora and Pammakaristos monasteries, although given the blurry borders of modern-day Ayvansaray, they are often not considered a central part of the neighborhood today.

In the seventh century, Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi mentioned glass ateliers in the neighborhood. Over the next century, there were an increasing number of ateliers and workshops operating in the neighborhood, such as the ceramic tile atelier founded by Damat Ibrahim Paşa in 1724. By the end of the eighteenth century, Ayvansaray had a lively manufacturing scene ranging from smaller crafts to large-scale operations such as shipbuilding. There were many shipyards, and their workers lived in the neighborhood. Until the area was cleared in the 1980s, Ayvansaray was colloquially known as the poorest neighborhood on the Golden Horn, along with Balat.

During the eighteenth century, another texture emerged in the neighborhood; the palaces in Ayvansaray were seen as resorts to get away from Topkapı Sarayı, the main residence, on special occasions like weddings and childbirths that called for a getaway from urban life. Hence, a residential scene developed in Ayvansaray. Sargis Saraf Hovhannesyan names many waterfront mansions that belonged to sultans in the eighteenth century, situated on the shore stretching from Ayvansaray to Eyüp. Growing urbanization on both sides of the Golden Horn, as well as the increasing importance of industrialism for Ottoman rulers, led to changes in the multi-faceted texture of Ayvansaray. The fusion of residential life with business operations was first replaced by mills and then by larger-scale industrial facilities towards the end of the nineteenth century. These facilities produced flour, lumber, soap, and other goods.

Ayvansaray took on various functions over the centuries as the neighborhood was almost entirely rebuilt after multiple fires that destroyed much of the Historical Peninsula. On July 27, 1729, the fire that broke out in Balat destroyed the shores of Ayvansaray, including much of the palace complex of Blachernae. Mustafa Cezar lists other fires in 1755, 1773, 1861, 1864, 1879, and 1911 that caused significant damage to the neighborhood. Especially during the 1861 fire, 219 houses and shops were destroyed, according to Zeynep Çelik. The severity of the damage is attributed to the fact that buildings were primarily composed of wood. The repetitive fires led to improvements in city planning; the rebuilt streets of Ayvansaray in the second half of the nineteenth century followed a grid-like structure, and masonry replaced wood in some rebuilt structures, except when it was unaffordable to a number of households in the neighborhood.

As a result of the demographic changes Ayvansaray underwent starting from the Byzantine era, the Greek Orthodox population decreased. However, an active parish that participated in the religious scene remained, due to the significance of the area for Orthodox culture. Although the fires destroyed a number of the remaining churches, some were rebuilt, and much of the nineteenth century urban texture that survived the 1861 fire was preserved. Today, we see a mixture of ruins from destroyed buildings as well as restored or rebuilt landmarks on the streets of Ayvansaray.

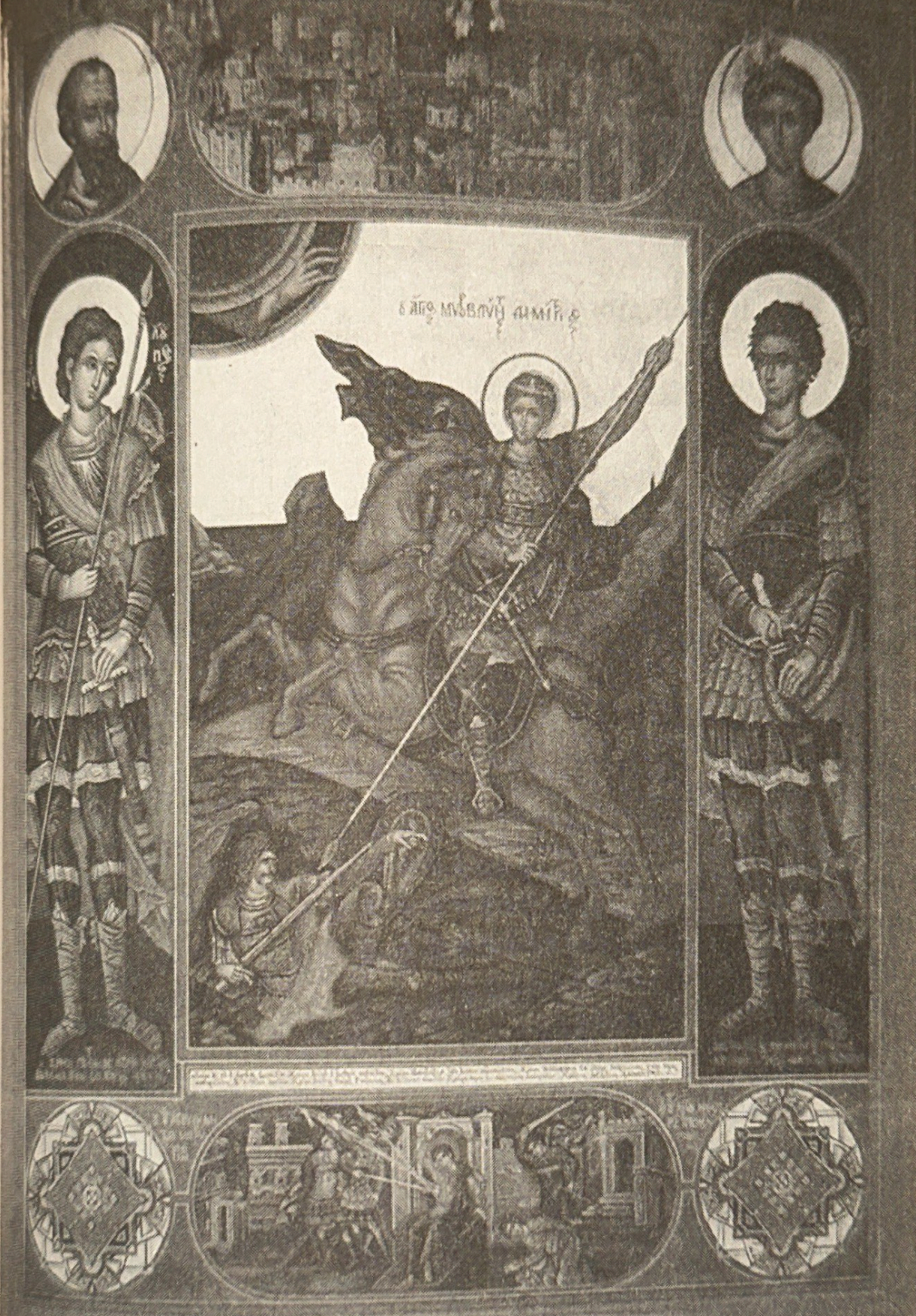

Hagios Demetrios Orthodox Church

The Hagios Demetrios Orthodox Church (Άγιος Δημήτριος, Ágios Dimítrios, Aya Dimitri) was built around April of 1204 as a tribute to Nikolas Kanabos, who only served as the Byzantine Emperor for a few days. While German architectural historian and archeologist Wolfgang Müller-Wiener states that the church was rebuilt by Georgeos Pepagomenos in the fourteenth century, while Alexander van Millingen, a German scholar of Byzantine architecture, writes that the ownership of the church was transferred to Georgeos Pepagomeos, and that a document indicates the church received a donation and was rebuilt in 1334. It is likely that Müller-Wiener and Millingen are referring to the same events. Due to financial debt, the church served under the jurisdiction of Meletios Pigas, the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria, from 1597 to 1601.

According to Müller-Wiener, the church was largely destroyed in the 1640 fire, and was rebuilt and destroyed once more in the 1729 fire. In 1730, it was rebuilt for the third and final time, and was restored in 1835. The restoration is recorded on an inscription on the church wall that reads: “This church was restored on July 20, 1835, during the reign of Patriarch Konstantios II.”

The Church of Saint Mary of Blachernae

The Church of Saint Mary of Blachernae (Θεοτόκος των Βλαχερνών) was very important to the Byzantines due to its proximity to the Palace of Blachernae. According to Byzantinist Raymond Janin, the original building was destroyed on June 29, 1434, when children accidentally set the church on fire while they were chasing pigeons in the courtyard. A smaller church was built on the site in the 19th century when the Ortodoks Kürkçüler Loncası (Orthodox Guild of Furriers) bought the land.

İştipol Synagogue

İştipol Synagogue was built by Greek Jews in the early 15th century and primarily served Shepardic Jews from the late 15th century on. A decree from November 1, 1898, indicates the synagogue burned down in a fire and was rebuilt. Today, the building is under preservation, and the synagogue is not open to worship.

Another Greek Orthodox church in Ayvansaray that is known to have once been the Patriarchal church is St. Dimitrios in Xyloporta (Ο Άγιος Δημήτριος στην Ξυλόπορτα). It was the seat of the Patriarch from 1597 to 1600, and was restored in 1835.

References

Achladi, Evangelia. "Rum Communities of Istanbul in the Nineteenth and Twentieth

Centuries : A Historical Survey." Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies

Association 9, no. 1 (2022): 19–49.

Byzantios, Skarlatos. Constantinople: A Topographical, Archaeological & Historical

Description Vol. 1. Translated by Haris Rigas. Istanbul: İstos yayın, 2019.

“İştipol Sinagogu.” Şalom Gazetesi. Accessed May 15, 2024.

Janin, Raymond, and Jean Darrouzès. Géographie ecclésiastique de l’Empire

byzantin. Paris: Institut français d’études byzantines, 1953.

Karaca, Zafer. İstanbul’da Tanzimat Öncesi Rum Ortodoks Kiliseleri. Istanbul: Yapı Kredi

Yayınları, 2008.

TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. “AYVANSARAY - TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi,”

“Palace of Blachernai.” The Byzantine Legacy. Accessed May 16, 2024.

Paspatis, Aleksandros. Balıklı Rum Hastanesi Kayıtlarına Göre İstanbul’un Rum Ortodoks

Esnafı, 1833–1860. Translated by Marianna Yerasimos. Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi, 2014.

Yaşar, Kübra. “19. Yüzyılda bir Haliç Yerleşimi Olarak Ayvansaray.’’ MA Thesis, Istanbul

Technical University, 2018.

Yörüten, Güneş, and Cenk Hamamcıoğlu. “19. Yüzyılda Düzenlenen İstanbul Tarihi

Yarımada’daki Ayvansaray ve Samatya Yangın Alanlarında Günümüzdeki Kentsel Dokuların İncelenmesi ve Karşılaştırılması.” Kent Akademisi 11 (33), no. 1 (May

2018): 11–28.

Comments